“If it is true that there are as many minds as there are heads, then there are as many kinds of love as there are hearts.” Tolstoy (2000: Anna Karenina p142)

Political Dimensions of Dioramas: The Personal Just Became Political Exhibits Theme

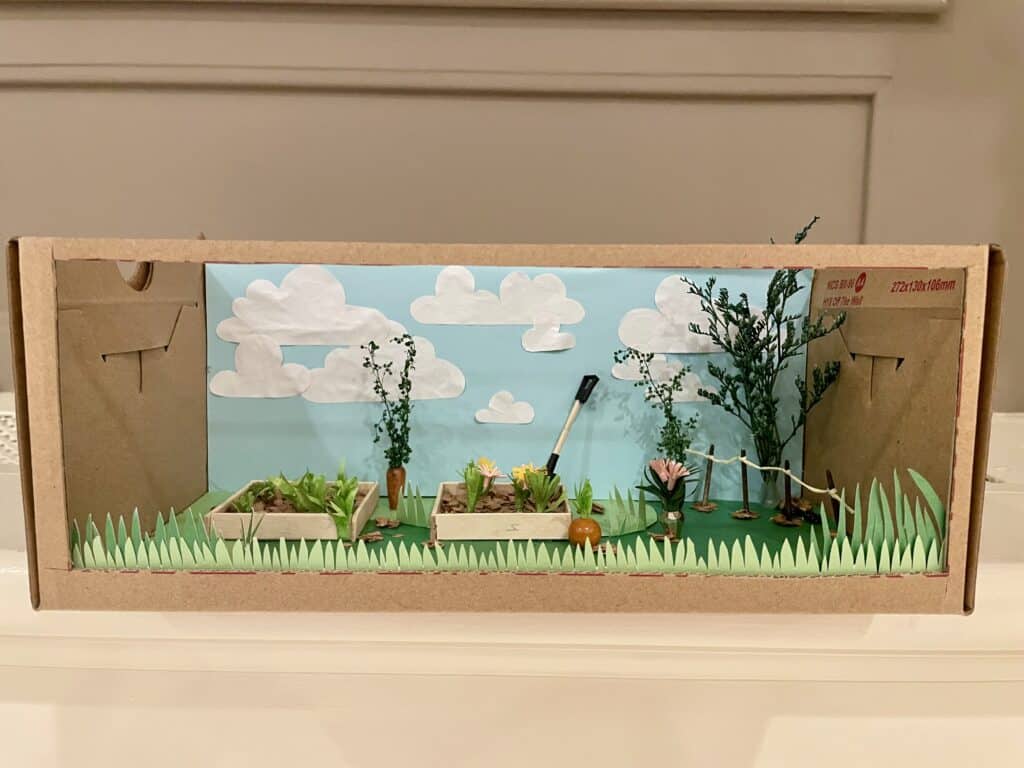

Connecticut College fall-semester students from diverse courses—HMD 225, 1069, PSY206, and 307—converge in a unique midterm project, crafting dioramas that encapsulate their academic insights and lived experiences. In an era dominated by AI and linear narratives, these miniature worlds offer a tactile, three-dimensional canvas for creative worldmaking and indigenous epistemology. The project celebrates each student’s distinctive voice, viewing plagiarism not merely as academic misconduct but as a psychoanalytic act of shoplifting—an unethical appropriation of another’s intellectual and emotional labour. This approach underscores the value of authenticity in academia, particularly vital in today’s digital landscape, and positions diorama as a powerful medium for expressing complex ideas and personal truths. The political implications of diorama creation are significant in an election year. Haraway (1984) provided a critical perspective on the political nature of natural history dioramas: “The diorama is eminently a story, a part of natural history. The story is told in the pages of nature and read by the naked eye. The animals in the diorama function as types, not as individuals” (p. 24). Insights can be extended to dioramas, created as political commentaries. Each element in these miniature scenes functions as a symbol that represents broader social and political realities. Baudrillard’s (1994) concept of hyperreality is particularly relevant in this context: “It is no longer a question of imitation, nor of reduplication, nor even of parody. It is rather a question of substituting signs of the real for the real itself” (p. 2). In their hyperreal representation of political realities, dioramas offer a unique medium for social critiques and political engagement.

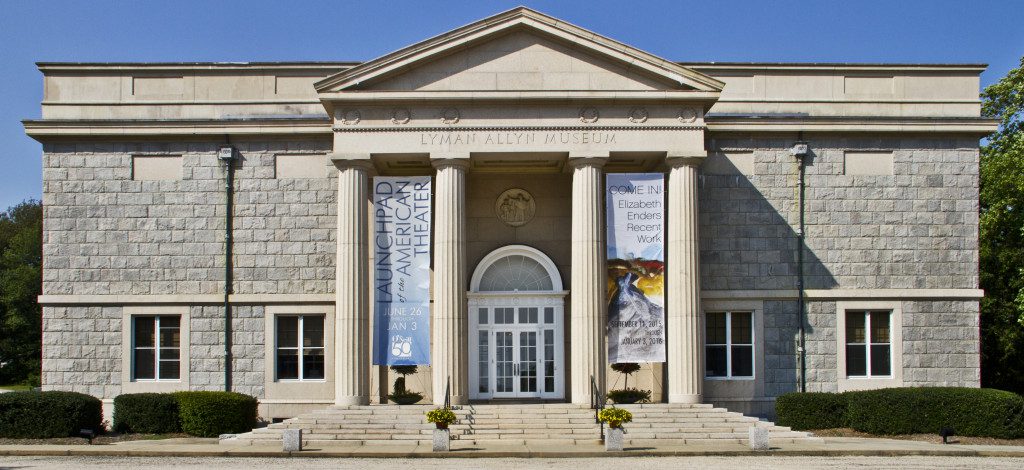

The intersection of personal expression and political engagement is powerful in Lyman Allyn’s exhibition Personal to Political: Celebrating the African American Artists of the Paulson Fontaine Press. This exhibit, featuring 46 fine art prints by 17 artists and a large-scale basketball pyramid installation by David Huffman, exemplifies how individual narratives can shape broader political discourse. Similarly, the students’ diorama project at Connecticut College embodies this “Personal to Political” theme, with each shoebox world serving as a microcosm of more significant societal issues. As Eileen Donovan, Director of Learning & Engagement, notes, these works “present a powerful array of figurative and abstract art”, mirroring students’ diverse approaches in their dioramas. Museum exhibitions and student projects demonstrate how personal experiences can transcend individual boundaries to engage with broader political and social narratives when curated and presented thoughtfully. This parallel underscores the diorama’s potential as a medium for political expression, allowing creators to construct miniature worlds that reflect and comment on the larger world around them, much like African American artists reshaping contemporary art in Lyman Allyn’s exhibition.

Dioramas

Diorama, a three-dimensional miniature scene, has long captivated the imagination of viewers and creators alike. Sugnet (1994) provides a comprehensive definition: “A diorama is a three-dimensional, miniature, life-like scene in which figures, stuffed wildlife, or other objects are arranged in a naturalistic setting against a painted background’ (p. 33). This narrative explores the multifaceted nature of dioramas and examines their roles in contemporary art, psychology, and political discourse. Through the lens of psychoanalytic theory and cultural anthropology, we investigate how dioramas serve as representations of reality and tools for psychological exploration. Claude Lévi-Strauss’s concept of bricolage offers a valuable framework for understanding the creation and interpretation of dioramas. Lévi-Strauss (1966) describes bricolage as the process of creating meaning from available materials: “The ‘bricoleur’ is adept at performing a large number of diverse tasks; but, unlike the engineer, he does not subordinate each of them to the availability of raw materials and tools conceived and procured for the project. His universe of instruments is closed, and the rules of his game are always to make do with ‘whatever is at hand’. (p. 17). In the context of dioramas, this process of bricolage is evident in the way creators assemble disparate elements to construct coherent narratives or scenes. Bennet (2010) notes that “dioramas are assemblages of objects, images, and texts that produce meaning through their juxtaposition and spatial arrangement” (p. 35).

Psychogeography Dimensions of Dioramas

The psychological implications of creating and viewing dioramas extend into the realm of psychogeography—the study of how physical and digital environments influence emotions and behaviour. Winnicott’s (1953) concept of transitional objects provides a valuable lens: “I have introduced the terms ‘transitional objects’ and ‘transitional phenomena’ for designation of the intermediate area of experience, between the thumb and the teddy bear, between the oral erotism and the true object-relationship” (p. 89). Dioramas are a form of spatial transitional phenomena, bridging internal and external realities. This concept finds a contemporary parallel in digital spaces, as Siddique (2024) observes: “The digital consulting room becomes a new kind of transitional space, where the boundaries between physical and virtual, internal and external, are constantly negotiated and redefined” (p. 178). This psychogeography echoes how dioramas offer a space where inner conflicts and desires can be externalised and explored. Freud’s (1920/1955) insights into miniatures further illuminate this: “Children do not distinguish sharply between living and inanimate objects, and they are especially fond of treating their dolls like live people’ (p. 141). This blurring of boundaries between animate and inanimate, both natural and represented, is central to the psychological power of dioramas and finds new expression in digital environments. The spatial arrangement within a diorama, such as the structure of a digital space, becomes a map of the psyche, where each element’s placement carries psychological weight, creating a miniature psychogeography that reflects and potentially reshapes the creator’s internal landscape.

Dioramas as Cultural Mediation

Lev Vygotsky’s theories of cultural mediation offer another valuable perspective on the function of dioramas. Vygotsky (1978) argued that “human learning presupposes a specific social nature and a process by which children grow into the intellectual life of those around them” (p. 88). As cultural artefacts, dioramas play a role in this intellectual and social development process. Reese (2007) applied Vygotsky’s ideas directly to museum dioramas: “Dioramas are mediating devices between visitors and absent worlds, whether these are in the past, in nature, or other cultures” (p. 50). The mediating function of dioramas makes them a powerful tool for education and cultural transmission.

Conclusion

Dioramas occupy a unique space at the intersection of art, psychology, and politics. As Wonders (1993) notes, “The diorama is a complex form of visual representation with a long history and a wide range of applications” (p. 12). The tactile, three-dimensional nature of dioramas offers a grounding counterpoint in the age of digital simulation and virtual realities. Through bricolage, we see dioramas as meaning-making, which assembles disparate elements into coherent narratives. As transitional phenomena, they provide a space for psychological exploration and growth. Cultural mediators facilitate the transmission of knowledge and values across generations and cultures. In the political sphere, dioramas offer a unique medium for commentary and critique. They allow the representation of complex political realities in tangible and accessible forms. As we navigate an increasingly complex political landscape, dioramas remind us of the power of visual storytelling and the enduring human need to make sense of our world through creative expressions in the space between us.

Biography:

Salma Siddique, PhD, an Associate Professor of Psychoanalytic Anthropology in Human Development at Connecticut College, USA, is a curious anthropologist of the human psyche, fascinated by the intersection of existential philosophy and the medical humanities. Through her research, she attempted to delve into the depths of psychoanalysis, psychotherapy, and anthropology, seeking to unravel the mysteries of our collective Contributors’ xv consciousness. Salma blends facts with fiction, creating friction that challenges established paradigms and illuminates new perspectives. Her fragmented pieces dance along the margins, blurring the boundaries between imagination and empirical data, defying potential pitfalls and betrayals of categorisation. With each mark, she expands our understanding of the relational other, inviting us to explore uncharted territories. She has a small private psychotherapy and supervision program in Scotland, UK.

Contact Details: E-mail: [email protected]

Department of Human Development and Psychology

Read Sole Searching – Stepping into Authenticity with Sneaker Box Dioramas in the Era of Fake Realities by Salma Siddique, PhD. Unpublished manuscript, Department of Human Development and Psychology, Connecticut College, New London, CT.